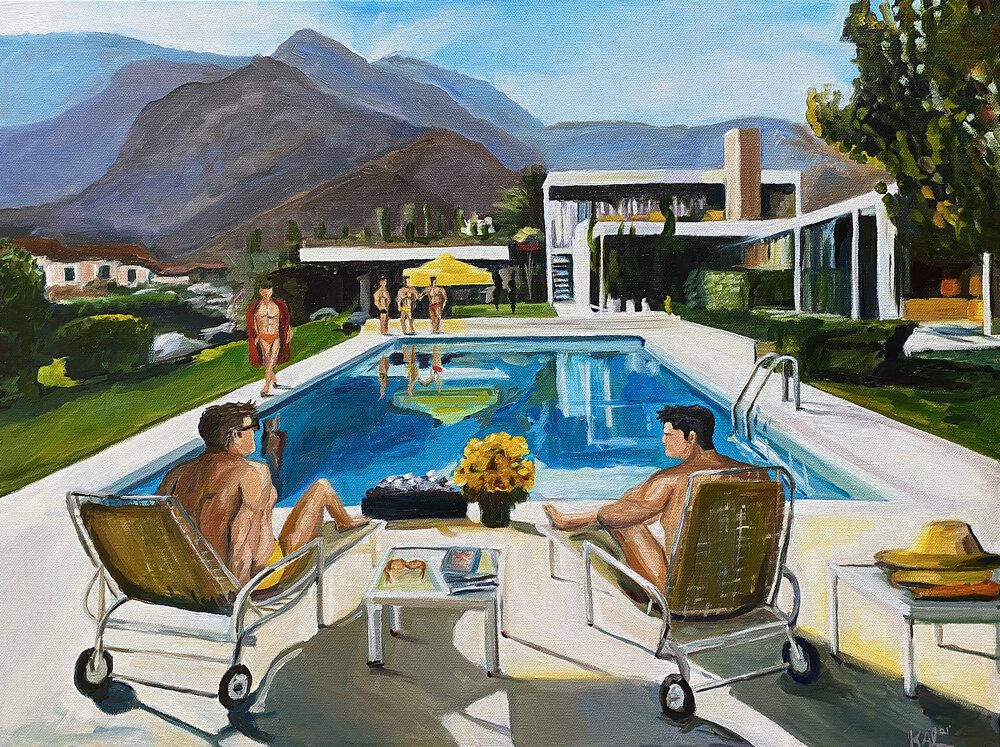

Selling something like a sunset

At what point does a bird eye’s view of our aesthetics encourage a curator’s approach to emotion?

There’s a soft filter set over the film, to smooth out the edges of plastic filler and soften the unnatural appearance of the cast’s extremities. Selling Sunset is a terrifying spectacle of poor taste and dubious reality, but I cannot stop watching. Like a fat Joan Didion, I sit in my New York apartment with no AC and consider coastal attitudes.

Intellect versus aesthetics, brunette versus blonde… these seem like the debates of older generations, and when I first moved to New York City it became clear that intellectualism is also an aesthetic, and ultimately that this kind of talk is pointless: every town is preoccupied with visuals. Unnaturally so, because social media has become the most common form of self-expression. Shit, man… even the absence of a discernible aesthetic is an aesthetic!

Much of my drinking follows the subsequent pressures of a curated life.

No great beauty or celebrated mind, I spend more time than I ought to considering how I come off. Everyone around me is similarly haunted by the ghost of the person they are trying to sell. In this sense, maybe the women of the Oppenheim Group are more honest, built in the image of how they/society—the distinction is tricky—feel a woman in Los Angeles should look. They are entirely self-possessed, for better or worse. And in our own dark, little ways, we each strive to be.

I compulsively watch The Kardashians, all of whom have become freaky BBL caricatures who dare not turn sideways. I ask aloud, “Are any of these people happy?” to the screen, to my friends, to myself.

Surely that much money could afford them something similar to joy, but the same television show that catapulted this clan to global fame now seems like a chore. Besides, would a happy person alter their appearance beyond recognition? (I’m asking!) The members of their inner circle similarly present faces a long walk from genetics, a disturbing case study in how beauty standards can become hyper-localized. Kind of like how when everyone started wearing chunky, white sneakers—you inevitably bought a pair of chunky, white sneakers.

It’s hard to imagine friends of Kim would’ve carved themselves so dramatically had they not been in such close proximity to the Kardashians: a group of independently unimpressive individuals who’ve reached astronomical levels of success, due to or in spite of their nips and tucks. But hey, I get it. It’s a human impulse to want to fit in. And our fundamental understanding of what humans actually look like is irreparably distorted.

For instance, my friend just showed me FaceTune, a phone app that requires no photoshopping experience to convincingly change your appearance—autocorrecting dimensions as you make your eyes or nose or chin smaller/bigger so the new ‘you’ always appears plausible—I was horrified, but also jealous. Had I known how easy and intuitive this evil technology was, I probably would’ve been using it from day-one. Now it feels too late to pretend to look like anyone but me.

It is curious, though, how we—nobodies—experience similar levels of dysmorphia as the rich and famous. Main characterization is endemic, particularly within digital interactions. For many, to unfollow or disengage online is tantamount to a drink in the face. I’m often the drinker in this hypothetical, because prior to the ‘Mute’ option becoming available, I would unfollow anyone I wasn’t speaking to consistently. (Also, I like to keep my following count ‘911.’) This move is usually interpreted as slight, but for me, few things are less personal than social media. I’ve always viewed it as a bandwidth issue; I cannot properly function for the people in my life when overloaded with the sensory and emotional content of others. What ever happened to party friends? There’s nothing wrong with party friends!

Not to mention social media’s effects on how we (think we) look(ed). A life with a camera always in-hand, my peers and I possess an abnormally acute understanding of the passage of time.

I wonder if my generation’s mental health crisis has anything to do with the refusal to accept what was previously inevitable.

JACOB SEFERIAN

“I look so much older than I did when I was nineteen,” a 23-year-old tells me. She shows me a saved Instagram story from years ago.

I admit that I don’t really see the deterioration, “but our phone cameras have gotten way more high-def since 2016. Maybe the lines you’re noticing have always been there.”

Such an extensive record of our lives can’t be healthy. Even our modern language is more dramatic, an outfit is now a look, a year or two an era—at what point does a bird eye’s view of one’s aesthetic begin to invite a curator’s approach to emotion?

I languish over what to wear, though no one expects me to be fashionable. I visually dissect the twenty pounds I put on and off, though it’s never really impacted how frequently I get laid. I overestimate my role in the lives of others, inflating the importance of my words and actions. Then I watch the curated realities of famous people and feel superior, thanking my stars I’m more enlightened than them.

More than anything, this lens of self is exhausting. And yet still my dates insist on talking about the material boundaries of their lives, friends refuse to see a different side and everyone is wearing perfectly calibrated outfits. All of which would be fine, if everyone didn’t seem so unfuckinghappy. Researchers warn not to confuse correlation with causation, but I wonder if my generation’s mental health crisis has anything to do with the refusal to accept what was previously inevitable, like the size of our pores or the crooks of our noses.

I can’t shake this feeling we’re being sold a life that only looks like the real thing.

Jacob Seferian is a writer and editor living in New York City. His work has appeared in over 13 magazines.

+ IMAGE : Kory Alexander