Jonesing for D

He was my OxyContin.

The following essay contains descriptions of substance abuse.

I was twenty-six when I found myself desperately seeking the attention of a man I’d met on Hinge.

Dylan was an unemployed bartender with a square-cut jawline, azure-blue eyes, and a vocabulary and intellect of an eighteenth-century poet. The last time I had felt this way was when I was high on dope. He was my OxyContin—my nightly escape—except the withdrawal symptoms were considerably worse.

Six years before, at twenty-one, I had my first encounter with skag. It started harmless, well, as innocently as a drug addiction could begin. Unable to shake the shame of my homosexuality, the disappointment toward my father’s own substance abuse issues, and my mother’s non-existent maternal instincts, I needed an escape.

Instead of seeing a therapist, I laid around in a dopamine trance because, consequently, pills were cheaper, quicker, and guaranteed to make the discomfort disappear. I had friends, albeit I never trusted them. The company I kept—serpentine addicts, graffiti writers with affluent parents, bohemian types who searched for enlightenment inside a pipe—aren’t the sort of people whom you’d leave alone in your house (unless you wanted your PlayStation stolen).

I haven’t touched an opioid since a near-fatal accidental overdose. I have been clean and serene for five years. The high I chase is one gleaned through mindfulness, ambitious creative pursuits, and travel. Swirling and puffing the misadventures, uncertainty, and career tribulations that have kept my mind empty—“My mind is a Teflon non-stick pan,” a Buddhist monk once instructed me—and the psychic vampires at bay.

I had mastered the art of healthy escapism. So I thought.

“Riley is always free,” my British friend’s boyfriend told me. We were out to dinner at a vegan restaurant celebrating a birthday. I was picking at my fries, sitting alone, and was the only one without a date. “If you need someone to go out with, text him.”

“Thanks,” I said, confused and paranoid, feeling like a third wheel.

Shortly thereafter, I signed up to Hinge. I was desperate to escape the isolation I’d felt at dinner. As I swiped nightly, I hoped, manifested, I would match with a man who could stimulate my brain and not my phallic one. Before signing up, I vowed not to have meaningless sex regardless of the intensity to succumb. If I needed a release, I had a perfectly functioning right hand.

Until Dylan blew up my phone: he was charming, slightly insecure and witty. He asked if the technological rose was a mistake. The last resort to running out of likes. In his display photo, a Pickachu onesie acted as his uniform and, thus, coquettishly asked me if it was a “Pikadude rose.”

As the weeks progressed, our conversations turned into long-winded love notes. Dylan showered me in affection: responding to each question with deep thought and self-awareness. Trapped in his Pokeball, I only thought about him and when my next hit would arrive. His beauty astounded me, while his Cheshire Cat eyes made me feel untrusting. Typically when a man is kind to me, they tend to bed me and then flee. There were red flags, of course. But I ignored them. (For instance, his past two relationships were with women.) He was my vagabond prince, having traveled the world with his mother as a child, searching for Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster.

Soon, Dylan’s messages turned into voice memos—sometimes 30 minutes long—that included renditions of our favorite poems (Bukowski’s “The Genius of the Crowd”; “Alone” by Poe; and Plath’s “Rectified”). I started to fantasize about our future together, re-listening to his husky voice, floating off, detached, in an oxytocin trance. I’d lay in bed, pillow clenched to my chest, dreaming of my head nestled between his armpit.

I wanted to slice him open and live inside of him: find refuge, solace and unconditional love.

After a six-hour phone conversation, where we’d planned to meet, he stood me up, and communication went mute. He’d confessed to suffering from introversion tendencies, so I rationalized and convinced myself it was too soon, moving too quickly, and Dylan would be in touch when ready.

Meanwhile, I started to believe I was an inconvenience. I spent entire days wondering if Dylan found me attractive. I felt him slipping away as though he’d cut our umbilical cord. Instead of giving him space, I sent him four messages in a row. I asked him to “Acknowledge me now or lose me forever,” a line I unabashedly stole from The O.C. In a cold sweat, I went to sleep shaking, withdrawing, waiting for a reply, jonesing for his adoration.

Following this was a week-long detox: I stopped taking my medication, seeing friends, accepting freelance work, showering. I had splitting headaches and heartaches; I listened to Oliva Rodrigo on repeat. I spoke about him ad nauseam. I wrote spells and tore them up. I watched trashy romcoms and would nefariously bellow at the unrealistic, psychologically damaging third-act, where the dispassionate male realizes he had foolishly let his lover go, reuniting at an airport, on a bridge, or at a wedding.

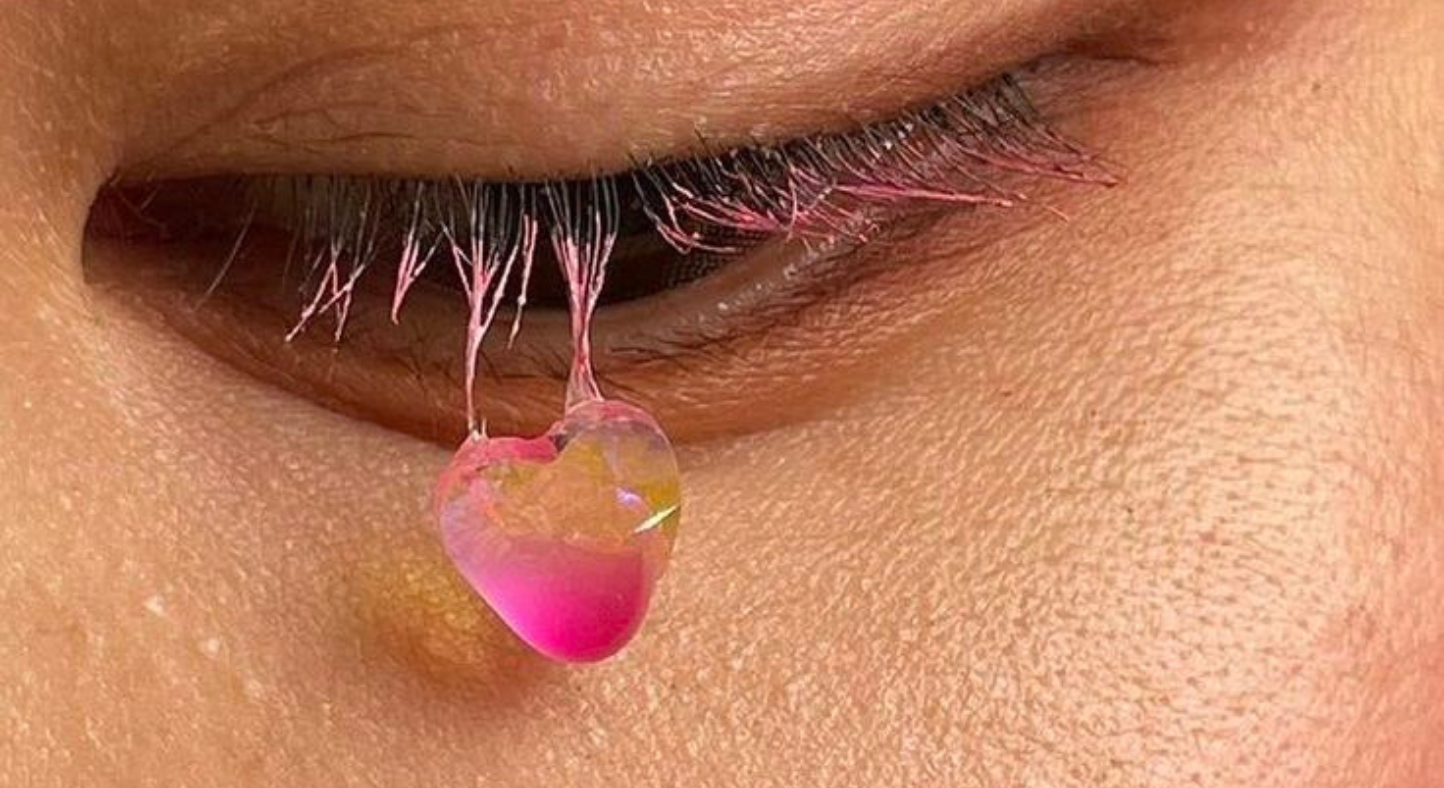

Escaping through a person is an unseemingly dangerous coping mechanism. Oxytocin, a hormone, is comparable to being hit with a cupid’s arrow dipped in Fentanyl. For men, spurts of the “love hormone” are released during hugging and orgasms, even while watching sport. For women: the latter applies with the inclusion of childbirth and breastfeeding. Regardless of gender, when attraction arises, your brain levitates out dopamine, progressing your serotonin levels to cause a variety of compulsive behaviors. Some fixate on sex, while others latch onto people.

“Has Dylan replied yet?” a discotheque DJ friend asked me.

“Not yet. I guess he didn’t appreciate the messages I bombarded him with. Who doesn’t like love notes in morse code?” I replied.

“He treats you like shit and you can do better.”

“Did you hear how scientists are trying to synthesize Oxytocin into a pill to treat PTSD?” I asked, drifting off.

If you would like support after reading this article, please utilise our free text line +61 488 848 782 [note: free in AUS only] to SMS chat with our team of sexologists, somatic healers and trauma counsellors. For instant support, call 131114 (AUS) / +1 800-273-8255 (US) or use this resource to determine the right number if you’re residing outside of these regions.

+ IMAGE: Rüdiger Trautsch