Afraid that life is going ‘too good?’

A story about losing your identity when you get healthy

Psychologists were part of my health care for a long time. I’d almost celebrated the fact that I hadn’t “had to see” a psychologist for six months. Not since I lost a loved one to suicide. But just last week I found myself scrolling the internet looking for the most pain-free therapy option available. For me, online video psych consultations are the right kind of novelty and give me the beauty of being in my own personal space whilst I’m processing my emotions. Sometimes I feel capable of progressing beyond my beautifully avoidant personality, but this week, I figure I need the comfort that distance provides someone like me.

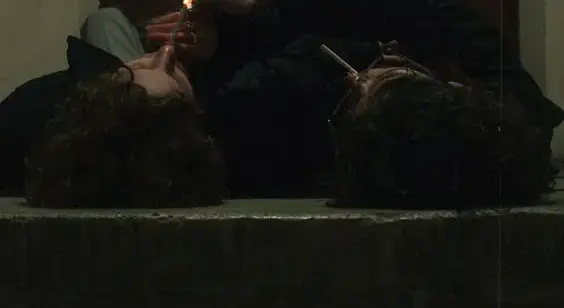

Avoidance and perfectionism have been instilled in me from childhood. But about six years ago, following a sexual assault, I was diagnosed with severe PTSD that quickly splintered itself into periods of psychosis and mania. The voice I lived with went from one that told me I was not good enough, to several different voices I didn’t recognise. It is almost hard to imagine the kind of nightmare I was living then at age 17, believing there were people following me, whispering dark orders in my ear as I hurried down the driveway. And trying not to let fear erupt onto my face as I squeezed a panicked smile out to my neighbour taking their bin out, convinced that if they knew I was unwell, I would die somehow. I smoked a lot of weed at the time to silence the intrusive thoughts, not realising how terribly aggressing it was to my deteriorating mental health. More often than not, I was having sleep paralysis where demons would open the locked sliding doors of my bedroom and climb on top of me, breathing on my neck. My life had slowly begun to feel like a prison, and my soul was inside of me, paralysed, screaming into a chamber of silence.

Because I refused to take medication, I lied my way through my mental health check-ups. As a student of psychology at the time and a natural actress, I managed to fool a lot of professionals giving them well-crafted and empathetically delivered monologues about how I was moving forward. I relished in my deceit, too. I’d played the perfect part, I’d thought. But I always found the session notes passed between my doctors challenging. The way they would write things like “anxiety” and “clinical depression” on a piece of paper as if it was meant to encapsulate the fear I had of driving my car in case I ran myself into a tree. I always wondered if anyone would suspect me of doing something like that on purpose. And I often fought with myself as to whether that kind of drastic action was what I really wanted. In any case, I, Sophie, ceased to exist as my own entity, overshadowed by what was given to me as my mental illness that I owned and tried to love. Assuming defeat, my last act of rebellion was concealing the enormity of my condition from the outside world, who received me largely as a sunny and optimistic being, albeit with poorly disguised manic highs – most recognisable to an outsider when I’d get my debit card out and start paying for other people’s things frivolously. ‘Fuck it, I’m generous’, I’d think, using some strange form of virtue signalling to pretend I wasn’t just finding new ways to self-harm.

I’d grown up so wide-eyed and craving life, that the highs weren’t as alien as the accompanying lows on the pendulum. The feeling of nothingness was most dissociating. I remember reading a passage from Corinthians in the bible in high school: “I see through a glass darkly.” It came to me – plucked itself almost – from the folds of my subconscious one day during this time. There was something maimed by my vision now in everything from the way I saw the moon, to the way holding someone else’s hand felt, that I couldn’t backspace. I had a few near misses with life itself that made me realise there was no deleting any of this or myself, I had to go through it and there was a beyond I had to trust in.

I’ve tried all sorts of therapies, including traditional psychology. I’ve refused medication and self-medicated with different substances all to keep me afloat. More potently I’ve used kinesiology, nature therapy, ayahuasca, medicinal mushrooms, gut biome healing, yoni mapping, journaling, acupuncture, cacao and physical mediums like yoga and dancing to creep out of my shame and unsafe spaces. And for the first time in years, I feel a sense that everything may finally be okay.

This sense of lightness and receptivity I have to life is marred by only one thing: a lingering sense that something bad is cued to happen any moment now. That’s part of why I’m seeing a psychologist again, to deal with an unexpected roadblock on my route to architecting a life I truly want: Cherophobia. Whilst cherophobia is not officiated on the DSM-5 (the book of all recognised disorders), Jessica Swainston, the Lead Psychologist for digital mental health innovator Cogenis simply puts cherophobia as a fear of happiness. For people with particularly traumatic lives, cherophobia is the belief that tragedy is looming just around the corner.

For me, cherophobia is having a panic attack because absolutely nothing “bad” happened at all for the past three weeks, and my physical being is confused. The truth is, I never imagined myself with the kind of stability I have now – a job I love, new creative opportunities presented to me every week, and a new-found self-belief that I am deserving of love and life in all forms.

Believing that we all deserve great things for ourselves is a strangely hard pill to swallow. In our subconscious, we can grow a whole variety of different belief systems that directly drive the formation of our reality. This is becoming more widely agreed upon by modern psychology, not as a victim-blaming activity, but as a direct pathway to reclaiming our personal power. Psychologist Jennice Vilahuer, author of Think Forward to Thrive, explains the way that the brain’s selective filtering system always looks to make our beliefs true: “When the brain is primed by a certain belief to look for something, it shuts down competing neural networks, so you actually have a hard time seeing evidence to the contrary of an already existing belief.” When you have been taught through learned experience that all you deserve or attract is catastrophe, it’s important to actively question these negative self-beliefs so you can truly move forward.

Interestingly, my psychologist includes the belief that I have cherophobia as something I need to stop investing in, reminding me that I don’t need a label or a box for my feelings to be validated. I’m working on letting go of all sorts of old stories. And to directly combat the feeling that things are going suspiciously well, I use affirmations and thought observation in powerful combinations. Every time I catch myself saying or thinking something that doesn’t attract growth, I stop myself and re-correct it on the spot. “Something bad is about to happen” becomes “I deserve and welcome all light the universe has to offer.” “I look hideous” instantly turns to “I am wildly beautiful inside and out.” Obviously, I don’t always wholeheartedly believe these new thought patterns as I introduce them, but over time, we can out crowd the negative thoughts so they stop appearing so frequently. It’s not about becoming a self-proclaimed God but it is about neutralising the idea that we are inherently broken.

If I’m being really honest, I don’t yet know who I am without mental illness. The story itself feels like a bootleg rags-to-riches tale, and there’s something sure-win about it in the way it buys me all sorts of social graces, be it allowances for my strangeness or just interesting conversation. Also, it’s the pain portal I lurk in between 9-5 for the purposes of education and creative inspiration. But for the first time in the non-linear experience that is existing on planet Earth (with or without mental illness), I get to ask myself new questions like, who am I as my most whole and receiving self? And for once, I don’t think there’s a right answer.